Creative Coding

Class page for IDM NYU DM-GY 6063 Creative Coding Section A Fall 2020

Some basic notes on electricity

Computers are great adding machines. They’re also great at comparing things that usually don’t work well together. Jim Campbell’s animation about various types of inputs and outputs demonstrates different ways we can use and think about transducers and actuators. Thanks to the magic of accessible computational media, we can get think about a wide varierty of applications for these tools. Visual arts, novel user interfaces, interactive experiences, these are just some of the kinds of things we can create while drawing on physical phenomena. Drawing on the real world makes our applications relevant and timely to folks.

At the end of the day, all we’re doing with a circuit or a computer is wrangling electrons. These little buggers want to move from a place of higher potential energy (often referred to as power) to a place of lower potential energy (often called ground). Some analogies for how electricty works in a circuit involve water, rocks, or buses. Because we only learned that electrons are negatively charged after we gave the names positive and negative to these things, there’s a diference in how physicists and engineers (and most folks) describe this phenomena.

When we describe electrical characteristics, we talk about voltage (measured in Volts), current (measured in Amps or Amperes), and resistance (measured in Ohms). Voltage is like the force of the electricity, the current is the amount of electricity, and resistance pushes back against the flow.

Ohms Law (V=I*R) is useful in theory, but not so much for day to day use. It’s useful for making sure you don’t light your LEDs on fire accidentally.

We always want our circuits (closed loops with a connection between power and ground) to have some sort of work for the electrons to do. This can be busywork (like a resistor), or actual work (like an LED), or behind the scenes work (operating logic gates). Without something to do, electrons get bored and start fires (aka short circuits). All voltage gets used up in a circuit, which is why you can’t bring your DVD player to France.

You should also keep in mind that that electricity is like a college student in that it follows the path of least resistance.

The last thing you need to know about circuit building is that all things must eventually connect to ground.

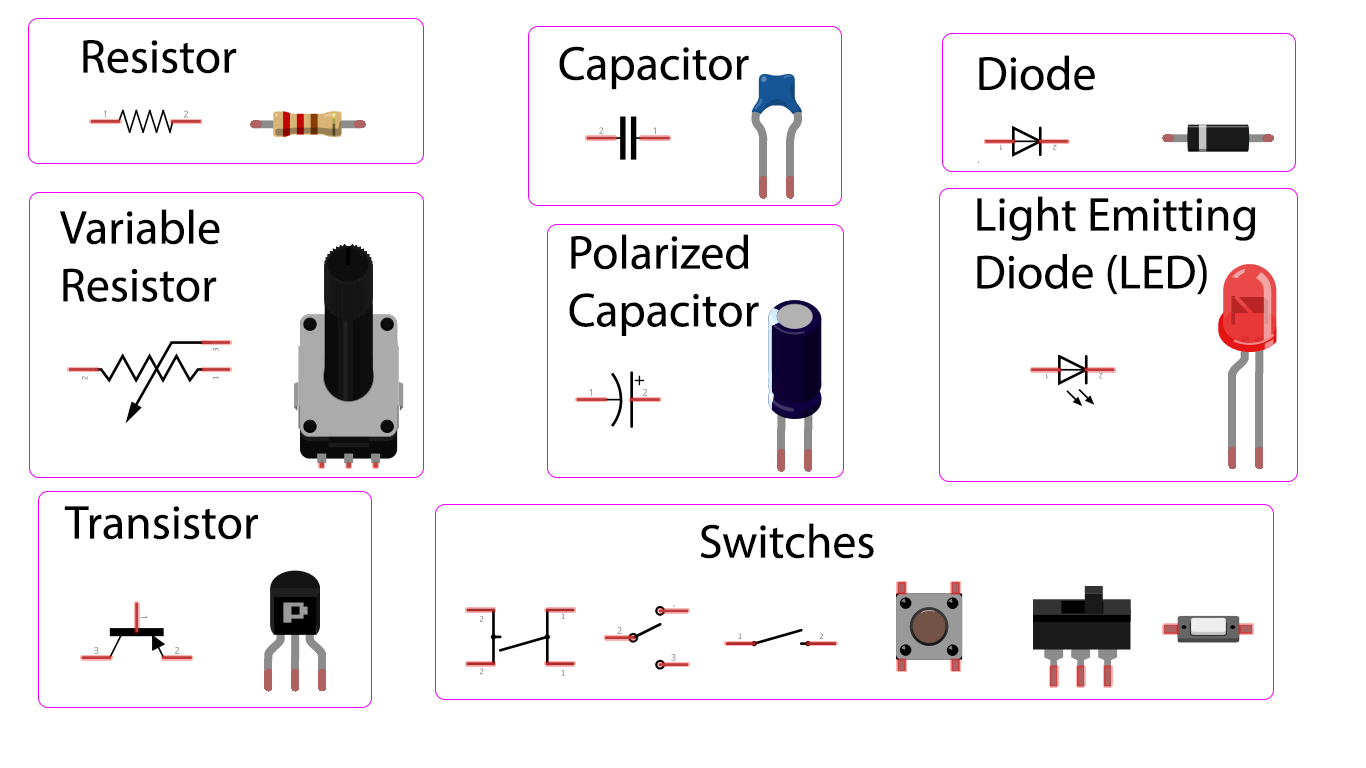

We use schematics to identify various components

Breadboards are our canvas. They’re the best. They allow us to change circuits quickly and easily. Underneath the plastic insulation, there are metallic strips that form connections which carry electricity. See what’s inside a breadboard for more.

Soldering is going to become your best bet at keeping things in place. Adafruit has an excellent guide to soldering.

We will be working with DC in this class. It’s what comes out of 9V batteries, USB cables, and the charger for your laptop. There’s also AC, it’s the stuff that comes out of wall sockets, runs along power lines, and has been used to electrocute an elephant. But don’t go there.

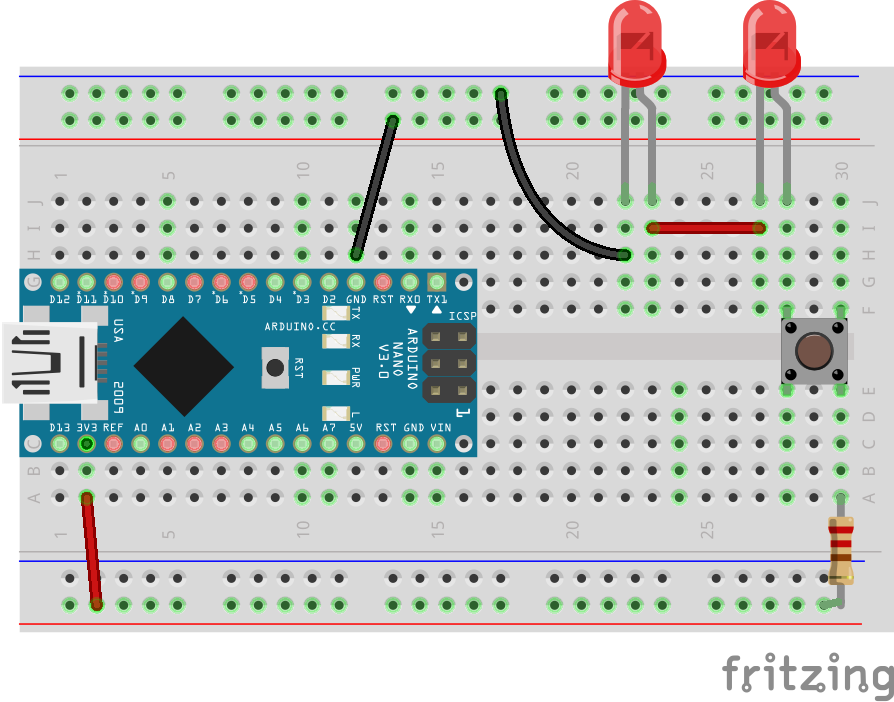

Here’s a simple circuit with an Arduino Nano

This circuit has 2 LEDs in series (for you CS folks, this is like &&)

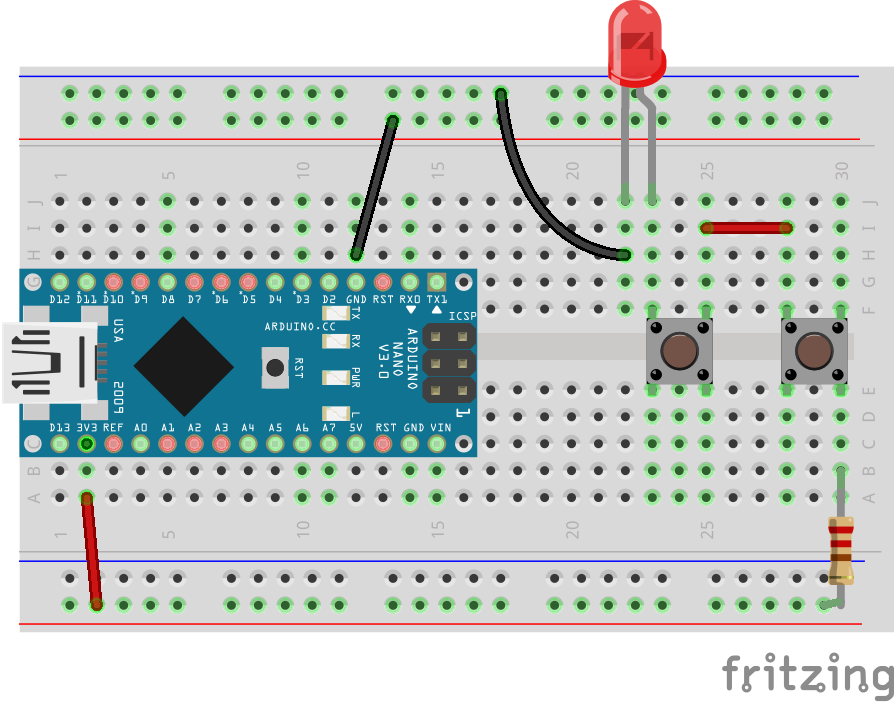

This circuit has 2 switches in series

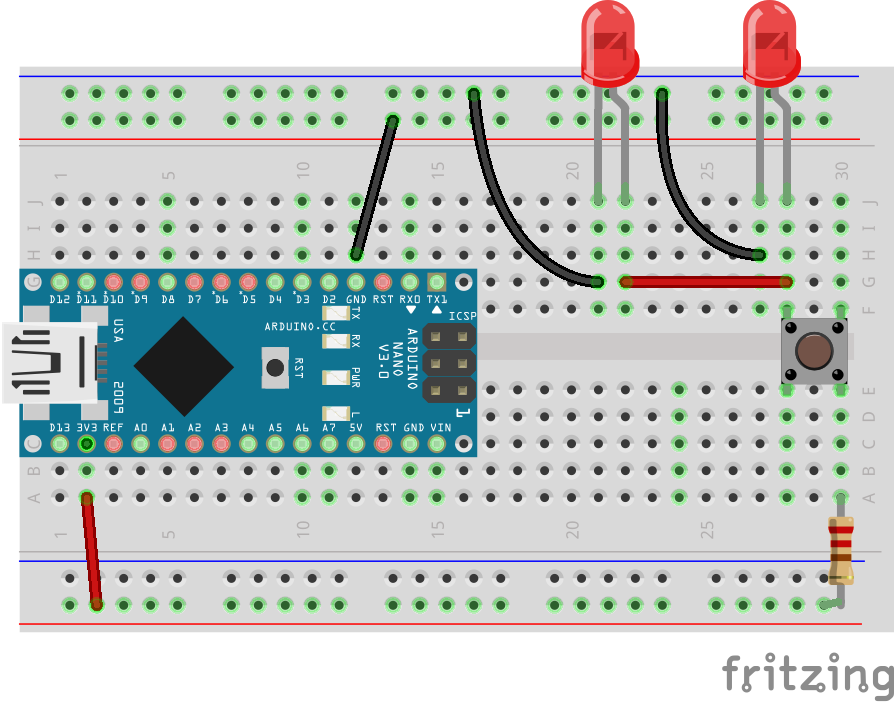

This circuit has 2 LEDs in parallel. The voltage drop across each LED is the same.

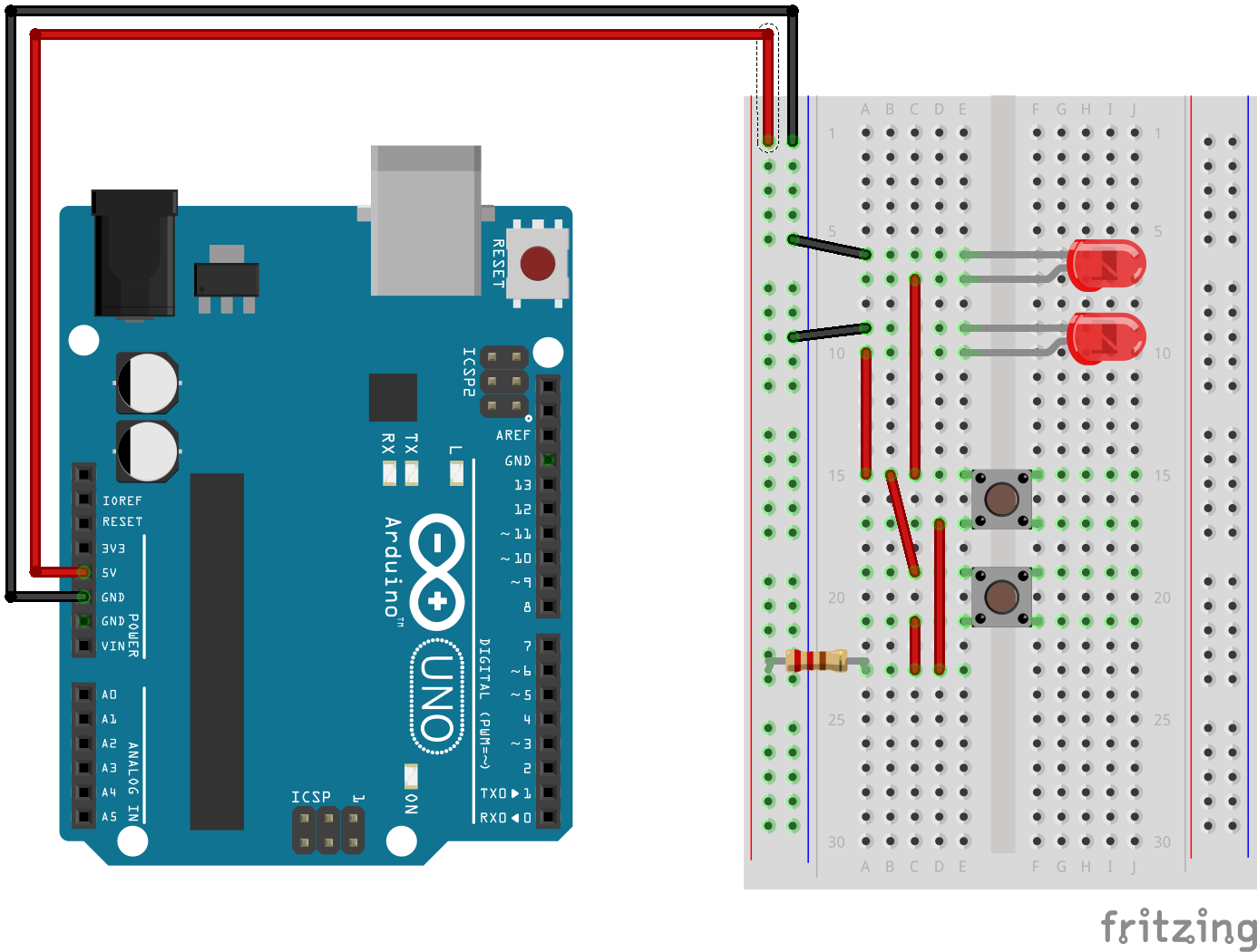

This curcuit has 2 LEDs and 2 switches in parallel (similar to || in programming)

Multimeters are great tools for figuring out what is going on inside a circuit. Adafruit has a very nice tutorial on how to use one.

Now that you have used a switch out of the box, make your own. Here’s an example of making a switch that doesn’t rely on your hands as a direct means of closing the circuit