The Browser and JavaScript

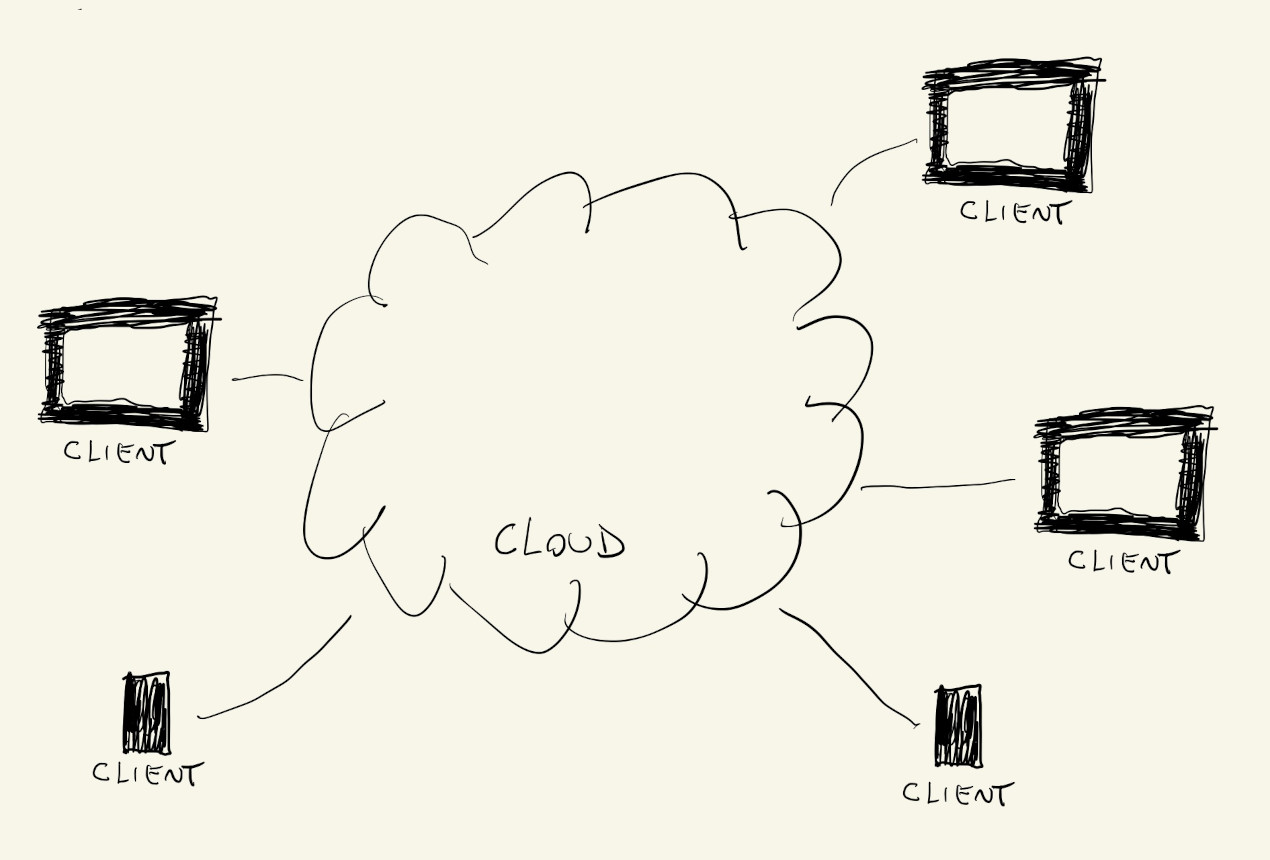

The Internet

Since JavaScript is a language that was originally designed to run on browsers over the internet, it could be useful to understand a little bit more about the internet and how it works.

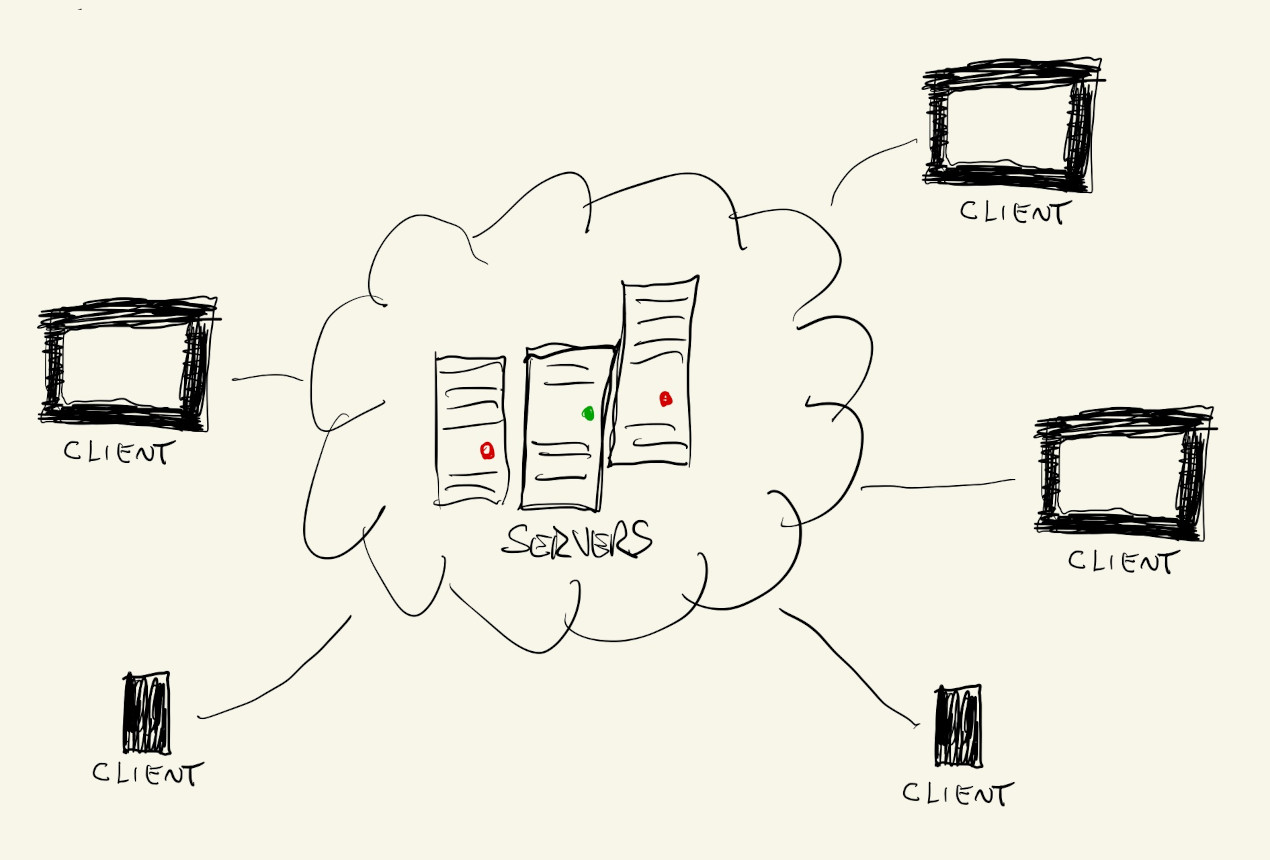

To put it simply, The Internet is just other people’s computers. There is no cloud, nor matrix, just a bunch of really big, hot and well-connected computers, called servers, that live in warehouses and store files that our phones and computers can download.

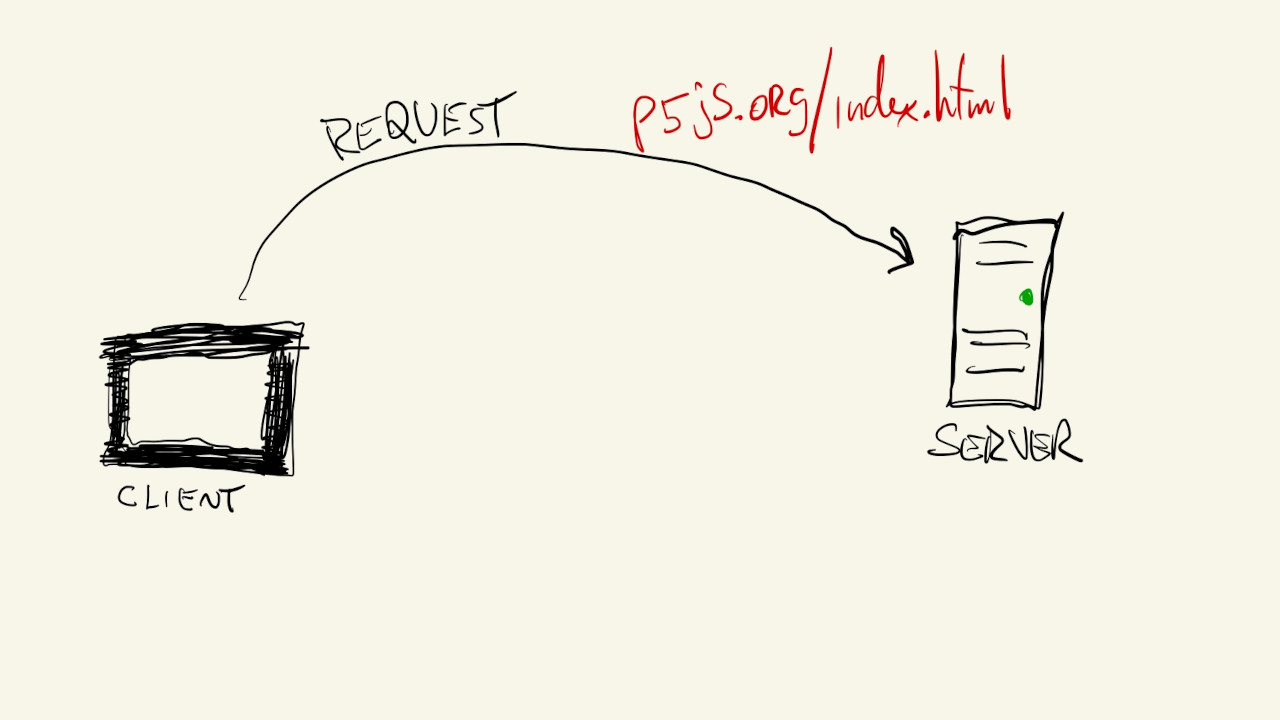

The process is similar for other types of services, but when we access a URL with our browser, our computer sends a request to one of these servers, asking for a particular file at the specified address. Requests made to URLs like p5js.org or nyu.edu are actually asking for a file called index.html that lives in the p5js.org (or nyu.edu) server computers.

The Browser

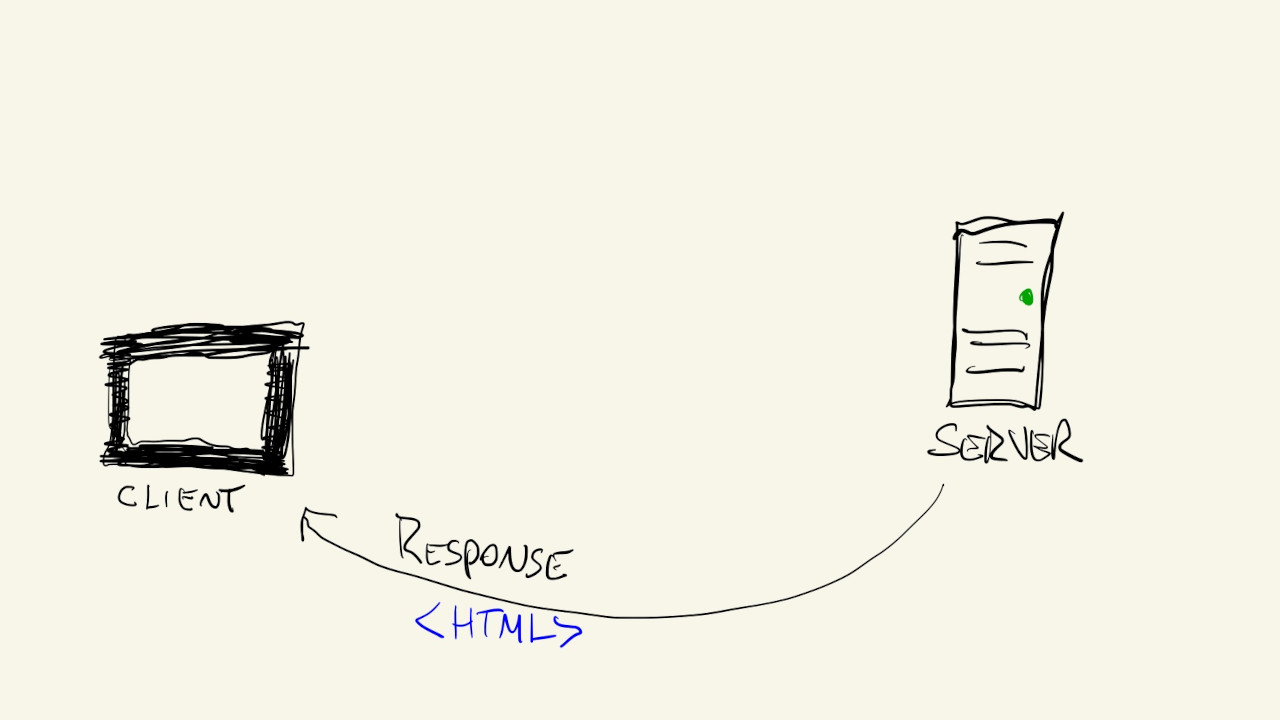

When our browser makes a correct and authorized request to a server, asking for an html file, the server responds with a text file with html code:

The html code might look something like this:

<html>

<head>

<title>My Homepage</title>

<link href="style.css">

<script src="sketch.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

Page Content

<img src="image.gif">

</body>

</html>

It’s not very important right now to understand html in detail. We should just know that it’s a language mostly used to specify the content that our browser should display for us and how that content should be organized on the screen.

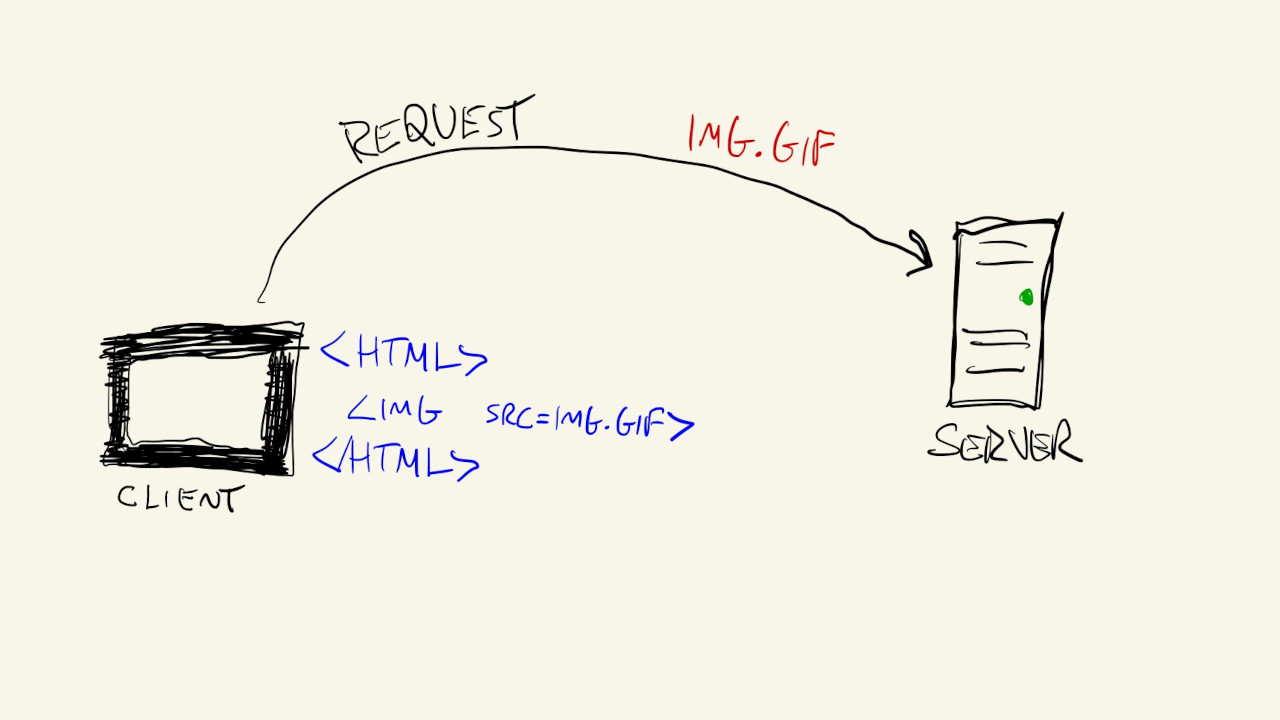

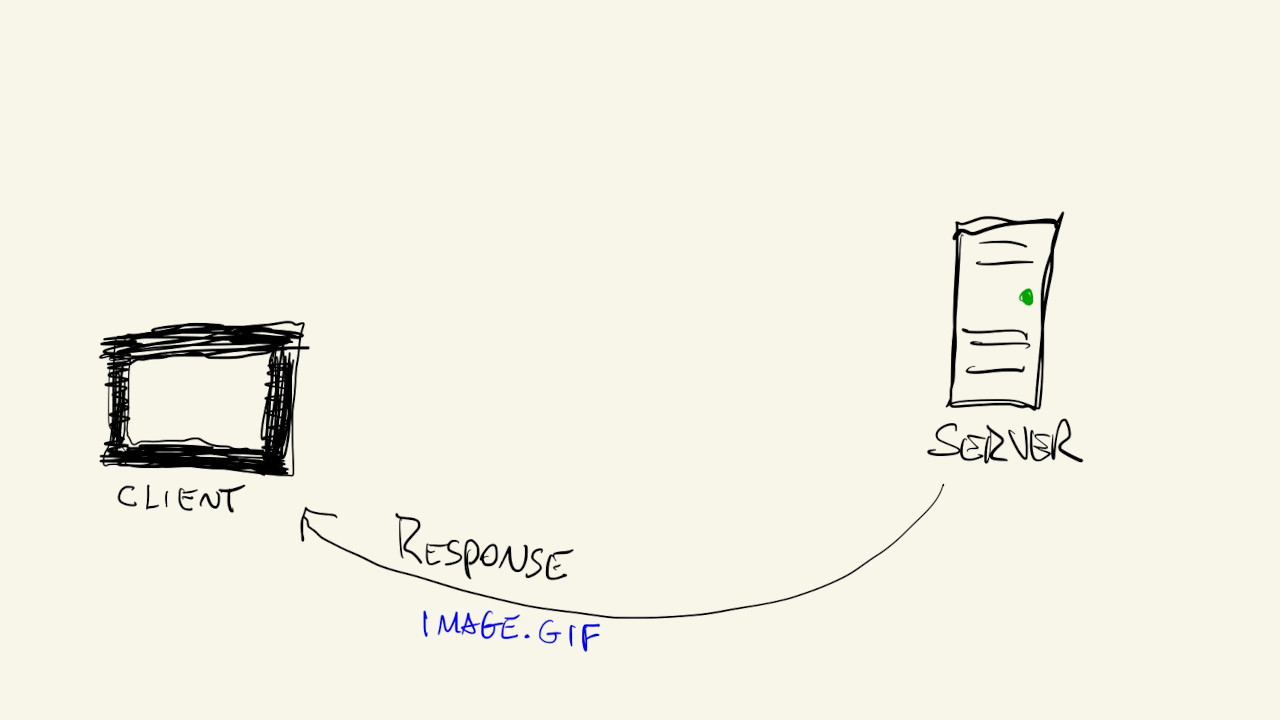

A lot of this content is text, and links, but more often than not, the html file will also reference other files, like image or video files. When the browser sees these references in the html code, it makes additional requests to the server, asking for those files.

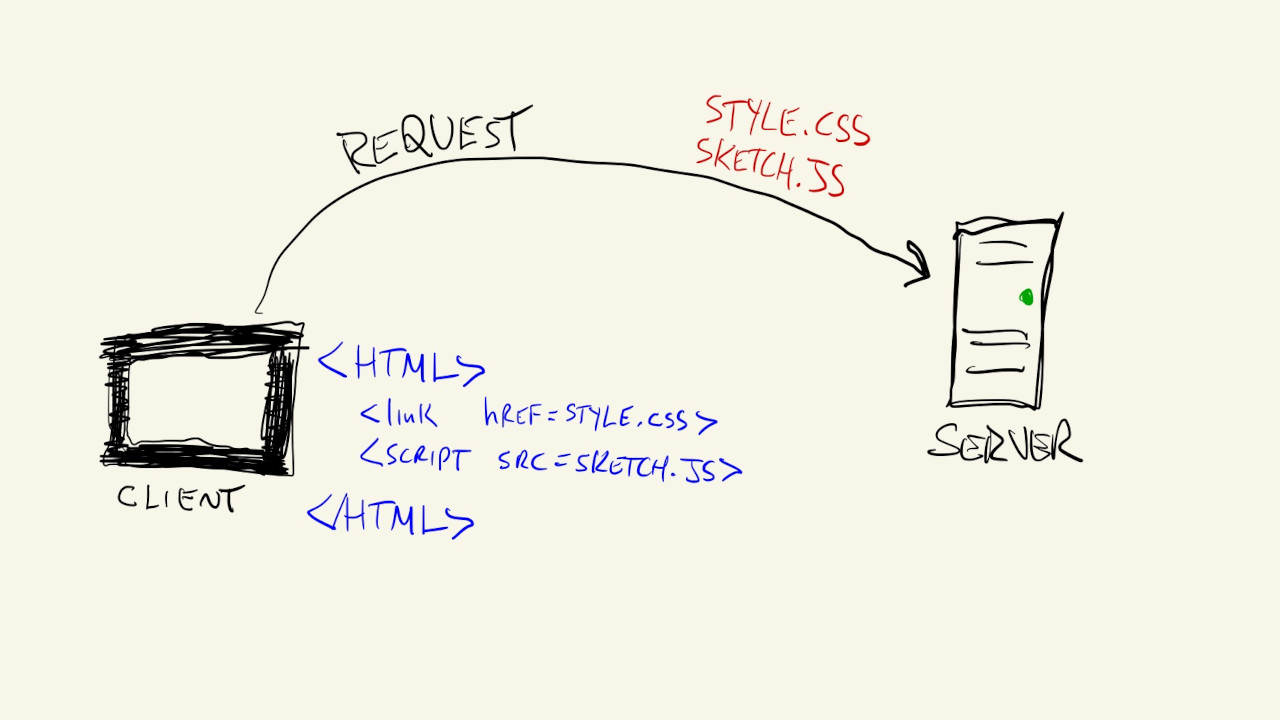

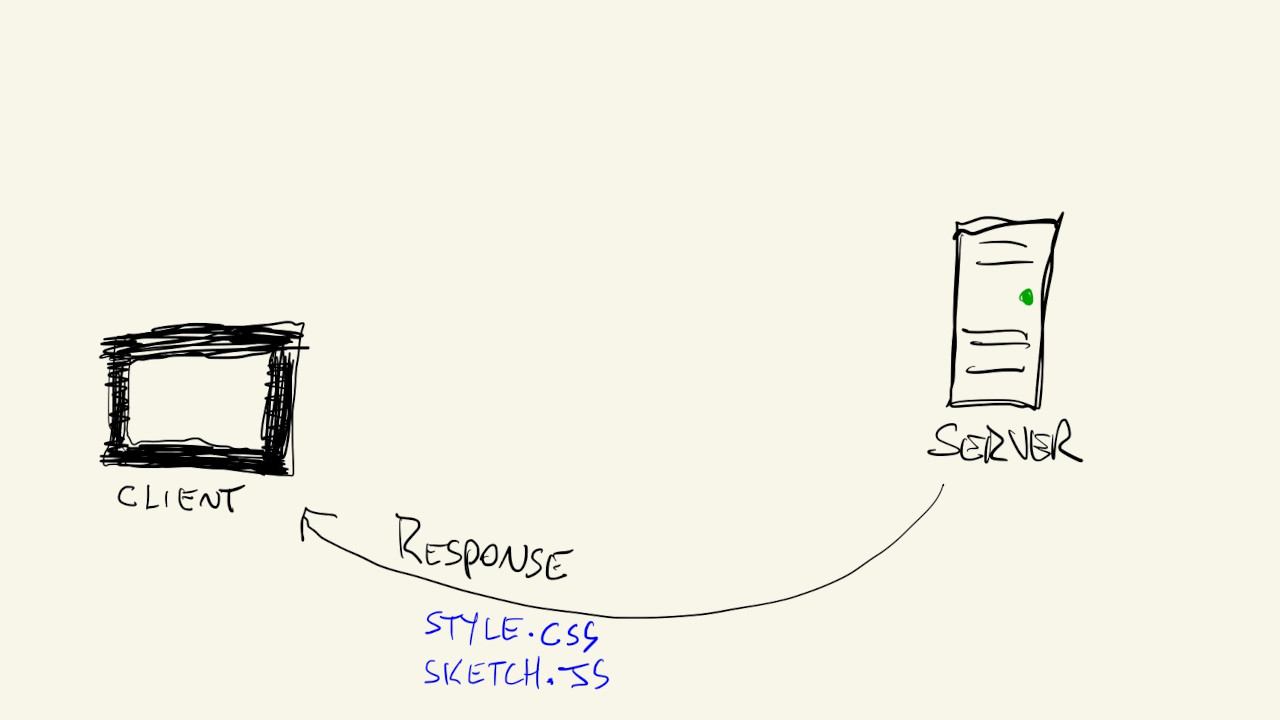

Other common types of files referenced by html are css files and JavaScript files. These are special because, unlike media files that the browser just has to show to us, they are files that change how the browser shows content and how it behaves.

css files usually specify the style of webpages. They tell the browser how to format the content in the html file: which fonts to use, what size the text should be, the colors of different elements, etc.

If a webpage was an apartment, the html file defines where the walls, doors and windows should go, while the css file specifies their materials and colors. Once the css file is downloaded, the browser has to go back through the content in the html file and apply the styles specified.

JavaScript files, on the other hand, describe how the browser should behave and what it should do with the content of the html file as a user interacts with it. Our analogy might be running out of steam, but if webpages were apartments, JavaScript might be the specification of what should happen when different light switches are pressed in a room.

JavaScript

In the early days of the internet, before JavaScript was a fully developed language recognized by all browsers, websites were pretty static. Once the html and css files were downloaded and the content of the page was styled and displayed, the browser’s job was done and we had on our screens the digital equivalent of a printed newspaper.

JavaScript gradually enabled websites to become more dynamic, allowing the content and style of a webpage to change based on user interaction.

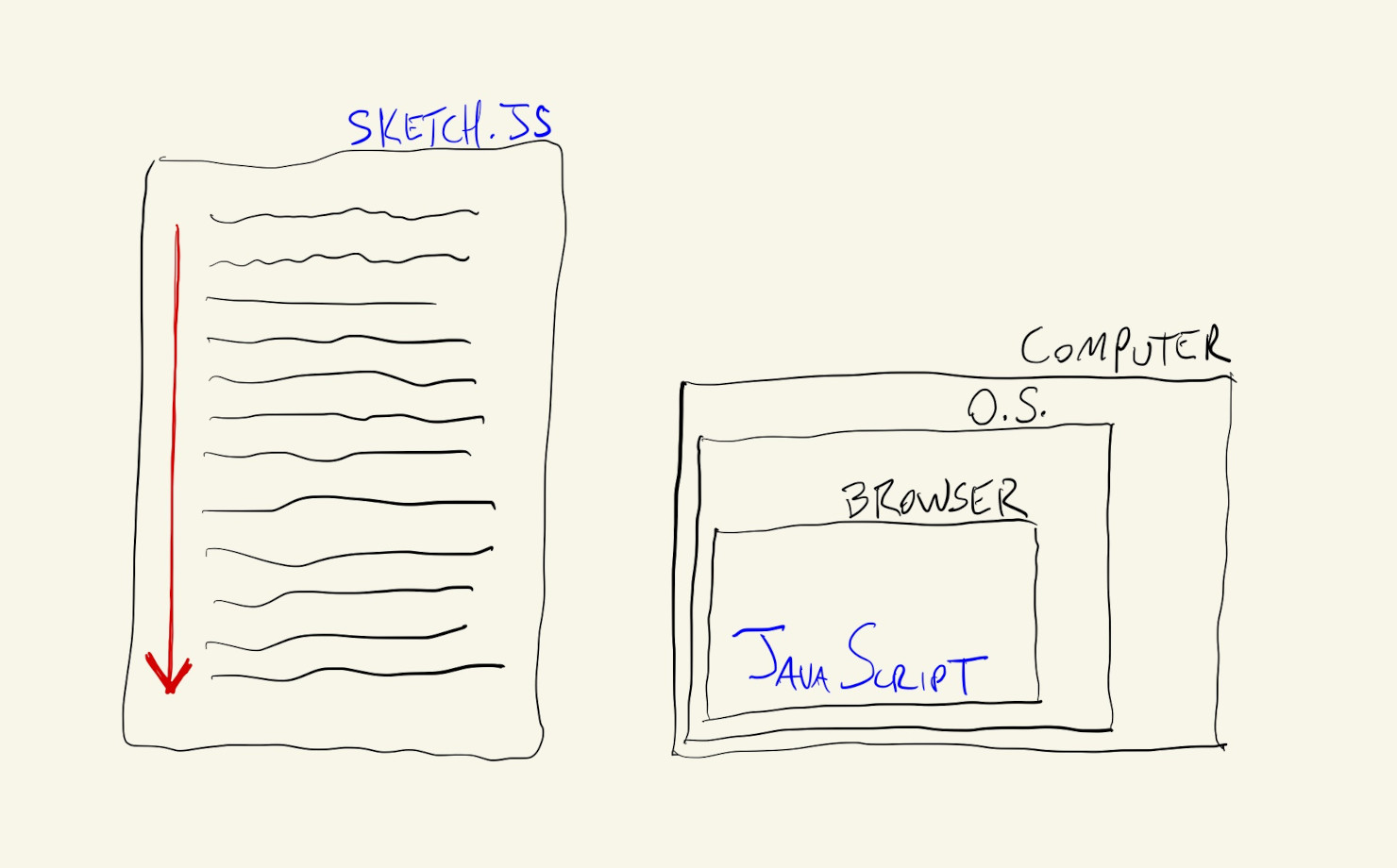

Once a JavaScript file (usually a .js file) is downloaded by a page, and while the html file and css file finish figuring out how to display the page’s content, the browser will start a separate parallel process to read and interpret the content of the JavaScript file.

This JavaScript interpreter (or engine), is an internal part of the browser that is responsible for going through the JavaScript file line-by-line and executing its commands. This is what it means for JavaScript to be an interpreted language: instead of running directly on the computer’s hardware, a JavaScript program needs another program to run it. It isn’t something unique to JavaScript, but does make it different from some programming languages, and is something we should keep in mind.

Nowadays, JavaScript is considered a robust, general purpose language that can be used to create almost any kind of programs, inside or outside a browser (but always with an interpreter). As such, we can find many resources in the form of libraries (reusable code) and frameworks (reusable code and predefined methodologies) that extend the language and make it easier for us to write certain types of programs without always starting from scratch.

p5js is an example of a JavaScript library. It’s focused on creative coding and making it easier for everyone to learn how to create interactive experiences using JavaScript.